What will happen to legacy broadcast groups when the lights go out?

Our smartphones have become our constant companions over the past decade, and it's often said that they've been so successful because they've absorbed the functionality of so many other devices we used to carry. PDA? Check. Pager? Check. Flash light? Check. Camera? Check. Mp3 player? Of course, and the list goes on. But alongside all that wearable technology, there's a broader effect on less wearable technology, and it's technology that even has a social aspect to it. Simply put, there is a generational divide that the smartphone has highlighted, between older people who consume media in a way born in the analog age, and younger people for whom their media experience is personalized and definitely non-linear. .

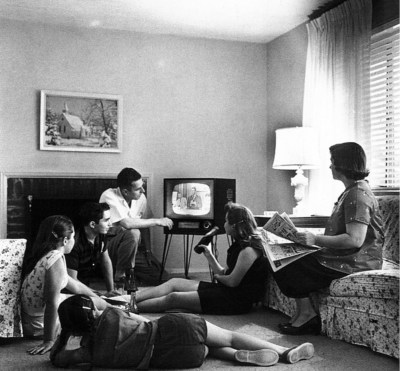

Children don't listen to the radio anymore We assume this is no longer a scene that plays out in many homes. Evert F. Baumgardner, Public Domain.

We assume this is no longer a scene that plays out in many homes. Evert F. Baumgardner, Public Domain.The effect of this has been to see a slow erosion of the once powerful reach of radio and television broadcasters, and with this loss listening has become less necessary for the old technologies they relied on. Which leaves a fascinating question here at Hackaday, what will happen to all this spectrum? Indeed, there is a deeper question behind all of this, does the low frequency spectrum still have that much value?

Previously, we had analog TV on multi-MHz channels spread across much of the UHF bands and a few small bits of VHF. Of these we had 20MHz of FM broadcast around the 100MHz mark, and disregarding shortwave, then one MHz of AM down about 1MHz. The Europeans also have a bonus band there: we have longwave, over 100kHz AM quality, centered roughly around 200kHz.

The last twenty years have seen a transition to digital for all television broadcasts, with for Americans at least a bunch of those UHF frequencies being reclaimed for data services. Radio has also gone digital, for Europeans with DAB in the 200 MHz band, but we still have a fairly thriving FM band even though governments are making noise to move FM stations to digital. Meanwhile, at the bottom of the dial, those AM and longwave bands are in terminal decline, with transmitters going silent across the board. Americans may still have more AM stations than Europeans, but we bet they aren't the best spots anymore.

Enthusiasts may point to digital AM systems such as DRM (Digital Radio Mondial) as their saviour, but can formatted music radio compete with streaming? In a few years it is likely that the AM and longwave broadcast bands will be empty, and perhaps not too far behind them the FM band as well. What happens then is the interesting part. Will they be resold for new uses, or will they sit idle, waiting for a new purpose? This is a question to which the answer is more complex than it seems, because it leaves the technical to the political.

How an auction broke an industry forever

Our smartphones have become our constant companions over the past decade, and it's often said that they've been so successful because they've absorbed the functionality of so many other devices we used to carry. PDA? Check. Pager? Check. Flash light? Check. Camera? Check. Mp3 player? Of course, and the list goes on. But alongside all that wearable technology, there's a broader effect on less wearable technology, and it's technology that even has a social aspect to it. Simply put, there is a generational divide that the smartphone has highlighted, between older people who consume media in a way born in the analog age, and younger people for whom their media experience is personalized and definitely non-linear. .

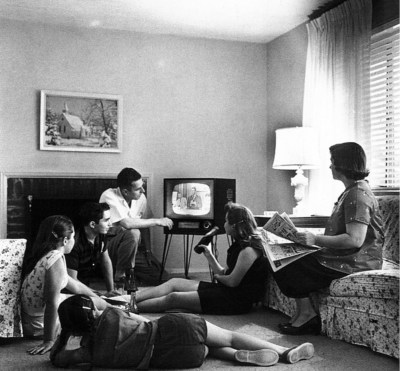

Children don't listen to the radio anymore We assume this is no longer a scene that plays out in many homes. Evert F. Baumgardner, Public Domain.

We assume this is no longer a scene that plays out in many homes. Evert F. Baumgardner, Public Domain.The effect of this has been to see a slow erosion of the once powerful reach of radio and television broadcasters, and with this loss listening has become less necessary for the old technologies they relied on. Which leaves a fascinating question here at Hackaday, what will happen to all this spectrum? Indeed, there is a deeper question behind all of this, does the low frequency spectrum still have that much value?

Previously, we had analog TV on multi-MHz channels spread across much of the UHF bands and a few small bits of VHF. Of these we had 20MHz of FM broadcast around the 100MHz mark, and disregarding shortwave, then one MHz of AM down about 1MHz. The Europeans also have a bonus band there: we have longwave, over 100kHz AM quality, centered roughly around 200kHz.

The last twenty years have seen a transition to digital for all television broadcasts, with for Americans at least a bunch of those UHF frequencies being reclaimed for data services. Radio has also gone digital, for Europeans with DAB in the 200 MHz band, but we still have a fairly thriving FM band even though governments are making noise to move FM stations to digital. Meanwhile, at the bottom of the dial, those AM and longwave bands are in terminal decline, with transmitters going silent across the board. Americans may still have more AM stations than Europeans, but we bet they aren't the best spots anymore.

Enthusiasts may point to digital AM systems such as DRM (Digital Radio Mondial) as their saviour, but can formatted music radio compete with streaming? In a few years it is likely that the AM and longwave broadcast bands will be empty, and perhaps not too far behind them the FM band as well. What happens then is the interesting part. Will they be resold for new uses, or will they sit idle, waiting for a new purpose? This is a question to which the answer is more complex than it seems, because it leaves the technical to the political.

How an auction broke an industry foreverWhat's Your Reaction?