Gauss' Judgment Day

May-June 2006 Volume 94, number 3

page 200Let me tell you a story, though it's such a well-worn nugget of math knowledge that you've probably heard it before:

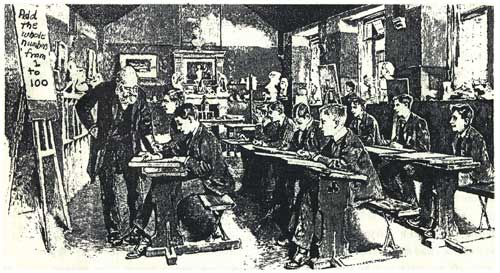

In the 1780s, a German provincial schoolmaster gave his class the tedious task of adding the first 100 whole numbers. The teacher's objective was to silence the children for half an hour, but a young student almost immediately produced an answer: 1 + 2 + 3 + ... + 98 + 99 + 100 = 5050. The evil one was Carl Friedrich Gauss, who would join the short list of candidates for the title of greatest mathematician of all time. Gauss was not a calculating prodigy who added up all these numbers in his head. He had a deeper idea: if you "fold" the series of numbers in the middle and add them in pairs - 1 + 100, 2 + 99, 3 + 98, etc. - all pairs add up to 101. There are 50 such pairs, and so the grand total is simply 50 × 101. The most general formula, for a list of consecutive numbers from 1 to n, is n(n + 1)/2.

The paragraph above is my own interpretation of this anecdote, written a few months ago for another project. I say it's mine, and yet I make no claim to originality. The same story has been told in the same way by hundreds of others before me. I've heard of Gauss' schoolboy triumph ever since I was a schoolboy myself.

Advertising rights

The story was familiar to me, but until I wrote it in my own words, I had never thought carefully about what happened in that class long ago. Now doubts and questions began to torment me. For example: how did the teacher verify that Gauss' answer was correct? If the schoolmaster already knew the formula for adding an arithmetic series, it would lessen the drama of the moment somewhat. If the teacher didn't know, wouldn't he spend his interlude of peace and quiet doing the same stupid exercise as his students?

There are other ways to answer this question, but there are also other questions, and soon I was wondering about the provenance and authenticity of the whole story. Where does it come from and how was it transmitted to us? Do scholars take this anecdote seriously as an event in the life of the mathematician? Or does it belong to the same genre as those stories about Newton and the apple or Archimedes in the bathtub, where literal truth is not the main issue? If we treat the episode as myth or fable, then what is the moral of the story?

To satisfy my curiosity, I started searching libraries and online resources for versions of Gauss's anecdote. I now have over a hundred copies, in eight languages. (The collection of versions is available here.) Sources range from scholarly histories and biographies to textbooks and encyclopedias, children's literature, websites, lesson plans, student articles, publications on Usenet newsgroups and even a novel. All of the accounts describe what is clearly the same incident - in fact, I believe they all ultimately derive from a single source - and yet they also show wonderful diversity and creativity, so that the authors have struggled to fill in the gaps, explain the motivations and build a coherent whole. narrative. (I soon realized that I had done some ad lib embroidery myself.)

After reading all these variants of the story, I still can't answer the basic factual question: "Did it really happen that way?" I have nothing new to add to our knowledge of Gauss. But I think I learned something about the evolution and transmission of these stories, and their place in the culture of science and mathematics. Well, I also have some stuff...

May-June 2006 Volume 94, number 3

page 200Let me tell you a story, though it's such a well-worn nugget of math knowledge that you've probably heard it before:

In the 1780s, a German provincial schoolmaster gave his class the tedious task of adding the first 100 whole numbers. The teacher's objective was to silence the children for half an hour, but a young student almost immediately produced an answer: 1 + 2 + 3 + ... + 98 + 99 + 100 = 5050. The evil one was Carl Friedrich Gauss, who would join the short list of candidates for the title of greatest mathematician of all time. Gauss was not a calculating prodigy who added up all these numbers in his head. He had a deeper idea: if you "fold" the series of numbers in the middle and add them in pairs - 1 + 100, 2 + 99, 3 + 98, etc. - all pairs add up to 101. There are 50 such pairs, and so the grand total is simply 50 × 101. The most general formula, for a list of consecutive numbers from 1 to n, is n(n + 1)/2.

The paragraph above is my own interpretation of this anecdote, written a few months ago for another project. I say it's mine, and yet I make no claim to originality. The same story has been told in the same way by hundreds of others before me. I've heard of Gauss' schoolboy triumph ever since I was a schoolboy myself.

Advertising rights

The story was familiar to me, but until I wrote it in my own words, I had never thought carefully about what happened in that class long ago. Now doubts and questions began to torment me. For example: how did the teacher verify that Gauss' answer was correct? If the schoolmaster already knew the formula for adding an arithmetic series, it would lessen the drama of the moment somewhat. If the teacher didn't know, wouldn't he spend his interlude of peace and quiet doing the same stupid exercise as his students?

There are other ways to answer this question, but there are also other questions, and soon I was wondering about the provenance and authenticity of the whole story. Where does it come from and how was it transmitted to us? Do scholars take this anecdote seriously as an event in the life of the mathematician? Or does it belong to the same genre as those stories about Newton and the apple or Archimedes in the bathtub, where literal truth is not the main issue? If we treat the episode as myth or fable, then what is the moral of the story?

To satisfy my curiosity, I started searching libraries and online resources for versions of Gauss's anecdote. I now have over a hundred copies, in eight languages. (The collection of versions is available here.) Sources range from scholarly histories and biographies to textbooks and encyclopedias, children's literature, websites, lesson plans, student articles, publications on Usenet newsgroups and even a novel. All of the accounts describe what is clearly the same incident - in fact, I believe they all ultimately derive from a single source - and yet they also show wonderful diversity and creativity, so that the authors have struggled to fill in the gaps, explain the motivations and build a coherent whole. narrative. (I soon realized that I had done some ad lib embroidery myself.)

After reading all these variants of the story, I still can't answer the basic factual question: "Did it really happen that way?" I have nothing new to add to our knowledge of Gauss. But I think I learned something about the evolution and transmission of these stories, and their place in the culture of science and mathematics. Well, I also have some stuff...

What's Your Reaction?

![Juno passes by Europa, revealing the mysterious and icy world [Updated]](https://cdn.arstechnica.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/PIA25330_-_JunoCam_Europa_-760x380.jpg)

![Three of ID's top PR executives quit ad firm Powerhouse [EXCLUSIVE]](https://variety.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/ID-PR-Logo.jpg?#)