How to repair? The death of patterns

There was a time when, if you were skilled with a soldering iron, you could easily open a radio or television repair business. You might not get rich, but you might just make a living. And if you had enough business acumen to make sales too, you might do well. These days, there aren't many repair shops and it's no wonder. The price of labor is rising and the price of things like televisions are falling every day. What's worse is that today's TV is not only cheaper than last year's model, but probably better too. On top of that, TVs are full of custom parts you can't get and packed into smaller and smaller packages.

For example, I saw a "Black Friday" ad for a 40-inch 1080p flatscreen monitor with a streaming controller for $98. Granted, it's not huge by today's standards and I'm sure it's not picture perfect. But for $98? These days, even a giant, high-quality TV can cost just over $1,000, and you can get something great for less than $500.

Looking back, a Sears ad displayed a lot on a 19″ color TV in 1980. The price? $399. That doesn't sound too bad until you realize that today it would be around $1,400. So, with a ratio of about 3.5 to 1, a $30/hour service call would be $105 today. So for a one hour service call with no parts, I could just buy this 40″ TV. Add even a single game or an hour more and I'm one step closer to big league TV.

Have you ever wondered how TV repair technicians know what to do? Well, for one thing, most of the time you didn't have to. A surprising number of calls would be something as simple as a frayed line cord or a dirty tuner. Bug-destroyed antenna wires were quite common. In the days of tubes, you could easily swap tubes to solve most real problems.

Back to shop: Riders and SamsMany stores would send a newbie out to check simple things, then bring everything else back "to the store" where someone who knew what to do would troubleshoot at the component level. Surprisingly, many televisions and other consumer electronics at one time had schematics inside the cabinet for service personnel. However, they were often cramped.

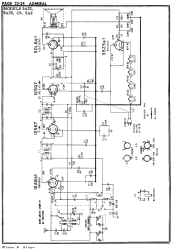

A Rider page for an Admiral radio

A Rider page for an Admiral radioThere were better options. Rider scraped data from every consumer electronic device they could find, and they published it all in large volumes, sometimes a total of 2,000 pages a year. Many of these old volumes are available on the Internet.

The other big service data publisher was Sams Photofacts. These folders would contain detailed information compiled on major televisions, radios, CB transmitters and, in a few cases, computers.

Sams is still around and will still sell his Photofacts to you, so they're harder to find online. However, there are some around if you look. You can also often buy used originals, just like you buy a used book. Apparently the copyright is exhausted on a few of the older ones and there are third parties who will also sell copies. You can also sometimes find them in libraries.

The Photofact files were generally very detailed. They would show disassembly instructions and, in addition to the schematic, would also show the nominal operating waveforms of the gear. It was not uncommon to see an image of a circuit board with a grid of letters and numbers to help you find parts on a cluttered board.

There was a time when, if you were skilled with a soldering iron, you could easily open a radio or television repair business. You might not get rich, but you might just make a living. And if you had enough business acumen to make sales too, you might do well. These days, there aren't many repair shops and it's no wonder. The price of labor is rising and the price of things like televisions are falling every day. What's worse is that today's TV is not only cheaper than last year's model, but probably better too. On top of that, TVs are full of custom parts you can't get and packed into smaller and smaller packages.

For example, I saw a "Black Friday" ad for a 40-inch 1080p flatscreen monitor with a streaming controller for $98. Granted, it's not huge by today's standards and I'm sure it's not picture perfect. But for $98? These days, even a giant, high-quality TV can cost just over $1,000, and you can get something great for less than $500.

Looking back, a Sears ad displayed a lot on a 19″ color TV in 1980. The price? $399. That doesn't sound too bad until you realize that today it would be around $1,400. So, with a ratio of about 3.5 to 1, a $30/hour service call would be $105 today. So for a one hour service call with no parts, I could just buy this 40″ TV. Add even a single game or an hour more and I'm one step closer to big league TV.

Have you ever wondered how TV repair technicians know what to do? Well, for one thing, most of the time you didn't have to. A surprising number of calls would be something as simple as a frayed line cord or a dirty tuner. Bug-destroyed antenna wires were quite common. In the days of tubes, you could easily swap tubes to solve most real problems.

Back to shop: Riders and SamsMany stores would send a newbie out to check simple things, then bring everything else back "to the store" where someone who knew what to do would troubleshoot at the component level. Surprisingly, many televisions and other consumer electronics at one time had schematics inside the cabinet for service personnel. However, they were often cramped.

A Rider page for an Admiral radio

A Rider page for an Admiral radioThere were better options. Rider scraped data from every consumer electronic device they could find, and they published it all in large volumes, sometimes a total of 2,000 pages a year. Many of these old volumes are available on the Internet.

The other big service data publisher was Sams Photofacts. These folders would contain detailed information compiled on major televisions, radios, CB transmitters and, in a few cases, computers.

Sams is still around and will still sell his Photofacts to you, so they're harder to find online. However, there are some around if you look. You can also often buy used originals, just like you buy a used book. Apparently the copyright is exhausted on a few of the older ones and there are third parties who will also sell copies. You can also sometimes find them in libraries.

The Photofact files were generally very detailed. They would show disassembly instructions and, in addition to the schematic, would also show the nominal operating waveforms of the gear. It was not uncommon to see an image of a circuit board with a grid of letters and numbers to help you find parts on a cluttered board.

What's Your Reaction?