Physics Meets Paleontology: The Highly Controversial Mechanisms of Pterosaur Flight

Zoom

Julius Csotonyi

Zoom

Julius Csotonyi

A group of researchers recently made an amazing discovery.

Using an innovative imaging technique, an international team of scientists has discovered remarkable details about the soft tissues of a pterosaur. Despite being around 145 to 163 million years old, the wing membrane and the webbing between the two feet managed to survive fossilization.

Armed with new data, the team used modeling to determine that this tiny pterosaur had the ability to launch itself from water. Their findings are published in Scientific Reports.

Fine detailsPterosaurs, an extinct type of winged reptile, were the first known vertebrates to soar and fly. Their sizes ranged from the tiny (a wingspan of 25 centimeters) to the absolutely enormous (a jaw-dropping wingspan of 10 to 11 meters). According to the new work's lead researcher, Dr. Michael Pittman, the tiny aurorazhdarchid that was studied could have fit in the palm of your hand. Of 12 well-preserved pterosaurs from the Solnhofen Lagoon in Germany, this was the only one with preserved soft tissue.

Dr. Pittman is a paleobiologist and assistant professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, and co-author Dr. Thomas G. Kaye is a Fellow of the Foundation for Scientific Advancement. The authors noted that this pterosaur is now among only six known pterosaurs with evidence of webbed feet and about 30 with wing membranes.

"We're constantly amazed at how stunning the preserved detail can be," Dr. Pittman told Ars, "which just keeps getting better as we refine the technique more and more."

The ability to detect these soft tissues and highlight them using laser stimulated fluorescence (LSF) is relatively new. LSF is a non-destructive imaging technique that has been taken to new levels by Dr. Pittman and Dr. Kaye.

“As part of a larger ongoing project,” Dr. Pittman said, “we have used LSF to reveal otherwise hidden soft tissue preserved in fossils. 'use LSF to study feathered dinosaurs and pterosaurs to better understand their biology and the evolution of flight.'

Ready to take off?In this case, understanding pterosaur biology involved determining whether this Late Jurassic creature could take off from water. Just because the pterosaur had webbed feet, the researchers pointed out, doesn't necessarily mean it spent any time in the water, or that it could get out of the water if it fell into it. p>

The work was incredibly difficult and potentially controversial. It is one thing to try to determine locomotion in animals whose skeletons mirror those that exist today; it's quite another matter when this creature has no modern analogue.

"There's a ton of debate about pterosaurs in general, about just about every aspect of their biology," Dr. Armita Manafzadeh told Ars. "And their joints are even more debated because they're just so weird."

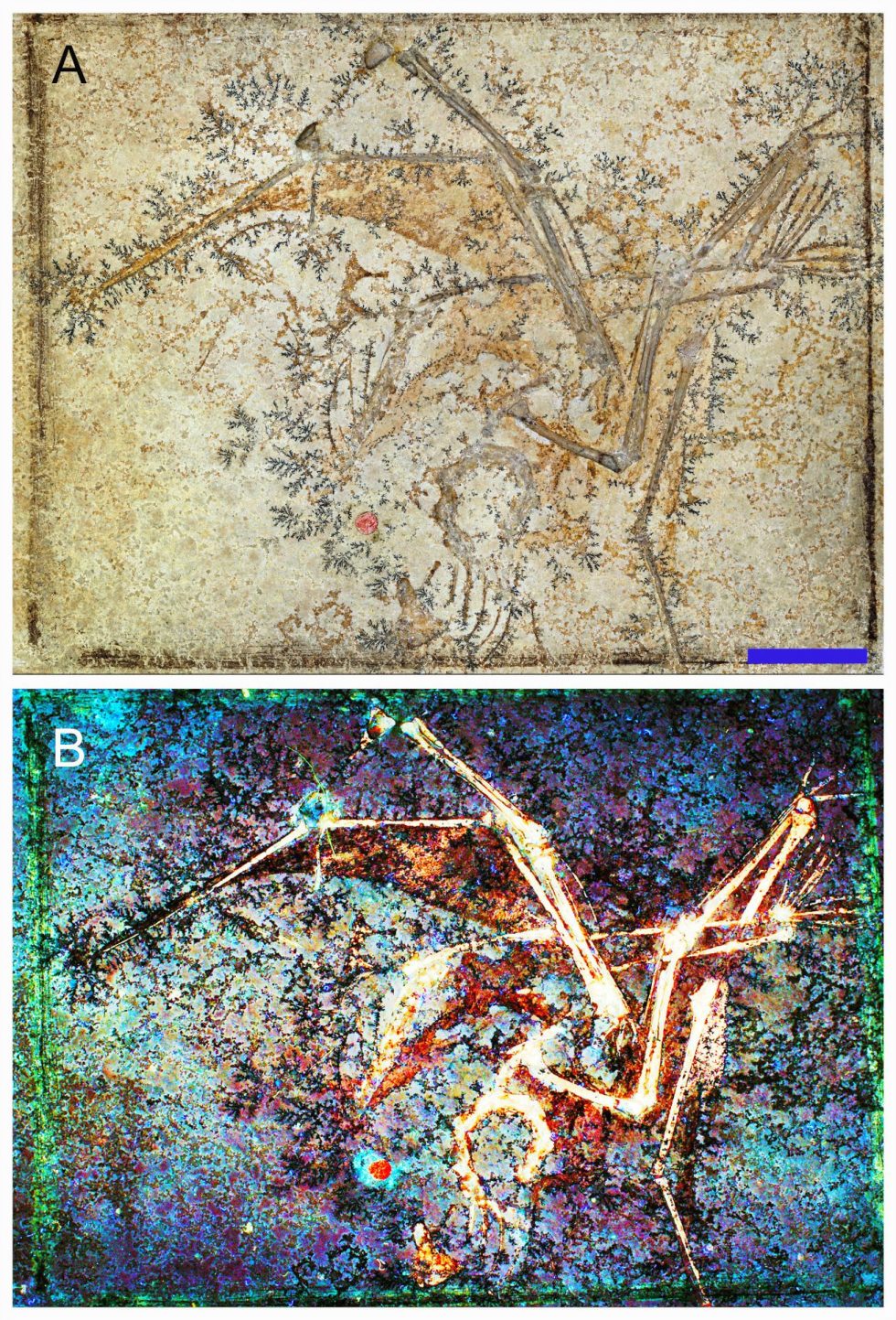

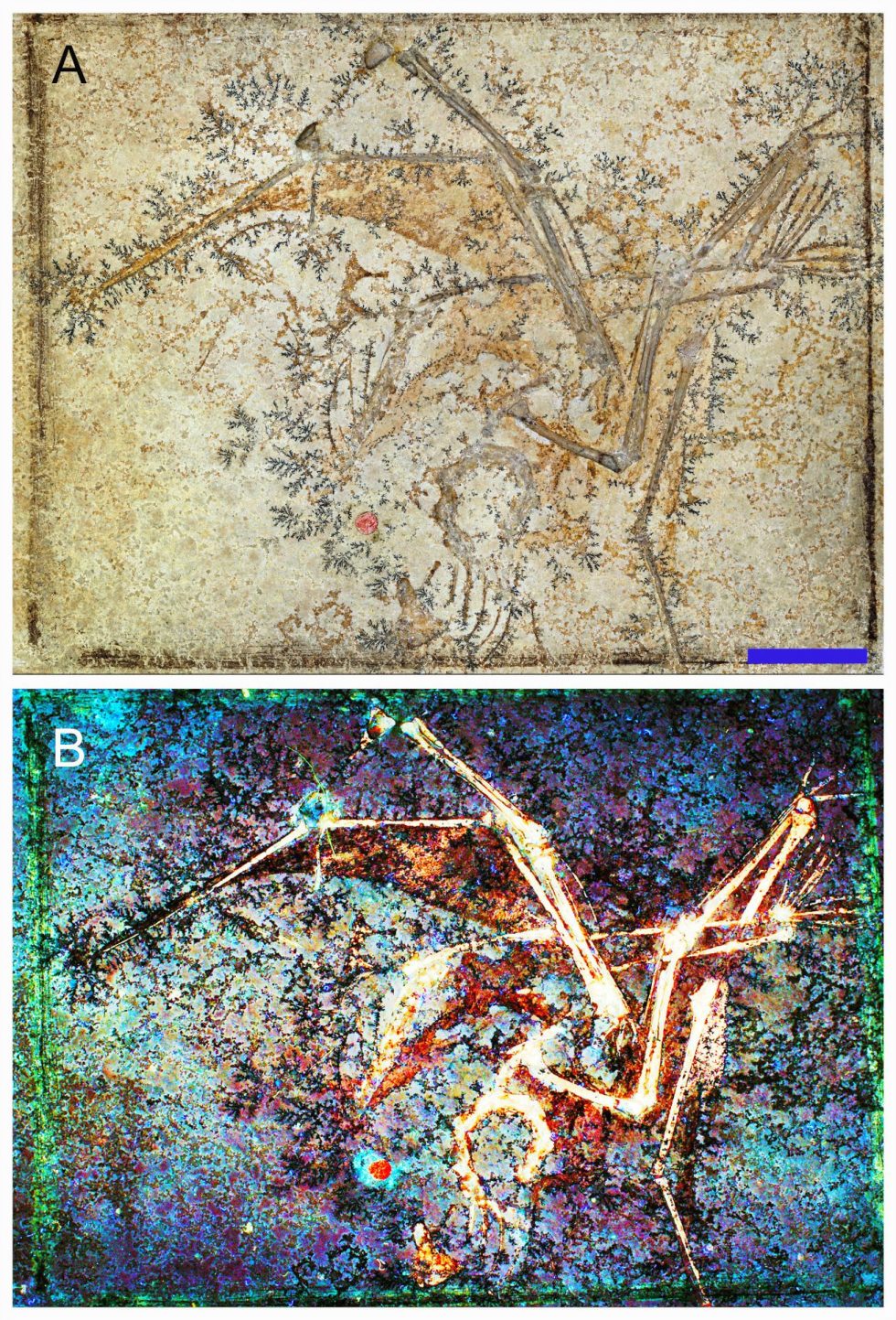

Enlarge / Skeleton and associated soft tissues of the aurorazhdarchid pterosaur fossil.

Pitman and. Al.

Enlarge / Skeleton and associated soft tissues of the aurorazhdarchid pterosaur fossil.

Pitman and. Al.

Dr. Manafzadeh, who was not involved in this research, is a Donnelley Postdoctoral Fellow and NSF Postdoctoral Fellow at the Yale Institute for Biospheric Studies. His

Zoom

Julius Csotonyi

Zoom

Julius Csotonyi

A group of researchers recently made an amazing discovery.

Using an innovative imaging technique, an international team of scientists has discovered remarkable details about the soft tissues of a pterosaur. Despite being around 145 to 163 million years old, the wing membrane and the webbing between the two feet managed to survive fossilization.

Armed with new data, the team used modeling to determine that this tiny pterosaur had the ability to launch itself from water. Their findings are published in Scientific Reports.

Fine detailsPterosaurs, an extinct type of winged reptile, were the first known vertebrates to soar and fly. Their sizes ranged from the tiny (a wingspan of 25 centimeters) to the absolutely enormous (a jaw-dropping wingspan of 10 to 11 meters). According to the new work's lead researcher, Dr. Michael Pittman, the tiny aurorazhdarchid that was studied could have fit in the palm of your hand. Of 12 well-preserved pterosaurs from the Solnhofen Lagoon in Germany, this was the only one with preserved soft tissue.

Dr. Pittman is a paleobiologist and assistant professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, and co-author Dr. Thomas G. Kaye is a Fellow of the Foundation for Scientific Advancement. The authors noted that this pterosaur is now among only six known pterosaurs with evidence of webbed feet and about 30 with wing membranes.

"We're constantly amazed at how stunning the preserved detail can be," Dr. Pittman told Ars, "which just keeps getting better as we refine the technique more and more."

The ability to detect these soft tissues and highlight them using laser stimulated fluorescence (LSF) is relatively new. LSF is a non-destructive imaging technique that has been taken to new levels by Dr. Pittman and Dr. Kaye.

“As part of a larger ongoing project,” Dr. Pittman said, “we have used LSF to reveal otherwise hidden soft tissue preserved in fossils. 'use LSF to study feathered dinosaurs and pterosaurs to better understand their biology and the evolution of flight.'

Ready to take off?In this case, understanding pterosaur biology involved determining whether this Late Jurassic creature could take off from water. Just because the pterosaur had webbed feet, the researchers pointed out, doesn't necessarily mean it spent any time in the water, or that it could get out of the water if it fell into it. p>

The work was incredibly difficult and potentially controversial. It is one thing to try to determine locomotion in animals whose skeletons mirror those that exist today; it's quite another matter when this creature has no modern analogue.

"There's a ton of debate about pterosaurs in general, about just about every aspect of their biology," Dr. Armita Manafzadeh told Ars. "And their joints are even more debated because they're just so weird."

Enlarge / Skeleton and associated soft tissues of the aurorazhdarchid pterosaur fossil.

Pitman and. Al.

Enlarge / Skeleton and associated soft tissues of the aurorazhdarchid pterosaur fossil.

Pitman and. Al.

Dr. Manafzadeh, who was not involved in this research, is a Donnelley Postdoctoral Fellow and NSF Postdoctoral Fellow at the Yale Institute for Biospheric Studies. His

What's Your Reaction?