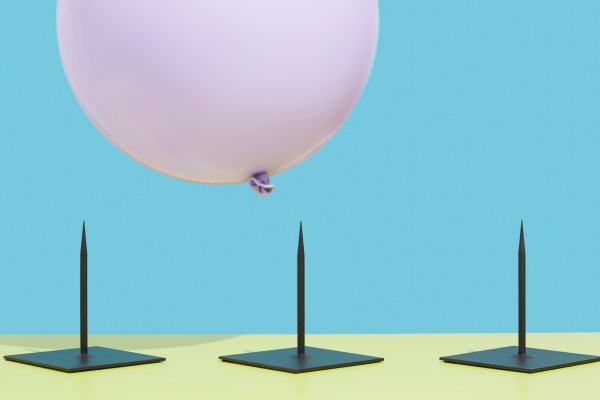

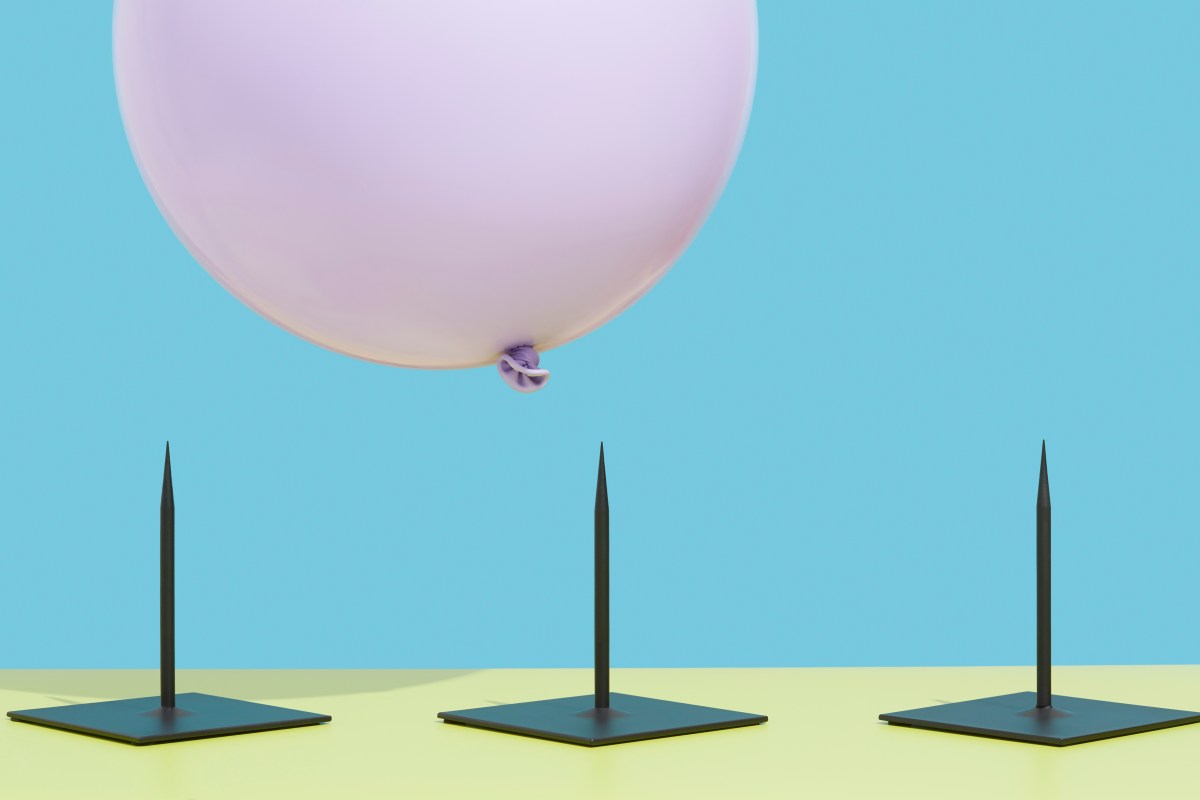

Fundraising steps aren't about dollar values - they're about risk

For a rapid increase in valuation, think, "What is the highest risk right now and how can I remove it?".

Haje Jan Kamps 7 p.m.

You've probably heard of pre-boot, boot, series A, series B, etc. These labels often aren't very useful because they aren't clearly defined - we've seen very small A-series rounds and huge pre-seed rounds. The defining characteristic of each cycle is not so much the amount of money that changes hands as the level of risk in the business.

In the course of your startup, two dynamics are at play at the same time. By understanding them deeply – and the connection between them – you'll be able to make much more sense of your fundraising journey and how to think about each part of your startup journey as you grow. and you develop.

Generally, in broad strokes, funding rounds tend to go like this:

The 4 Fs: Founders, Friends, Family, Fools: This is the first money that comes into the business, usually just enough to start proving some of the core technology or business dynamics. Here the company is trying to build an MVP. In these rounds, you will often find angel investors of varying degrees of sophistication. Pre-seed: Confusingly, this is often the same as the above, except it is done by an institutional investor (i.e. a family office or venture capital firm focusing on early stages of business). It's usually not a "round robin" - the company doesn't have a formal valuation, but the money raised is on a convertible or SAFE note. At this stage, businesses are generally not yet generating revenue. Seed: These are usually institutional investors who invest larger sums of money in a company that has begun to prove some of its momentum. The startup will have some aspect of its operational business and may have test customers, a beta product, an MVP concierge, etc. It won't have a growth engine (in other words, it won't yet have a repeatable way to attract and retain customers). The company works on active product development and pursues product-market fit. Sometimes this round is priced (i.e. investors trade a valuation of the company), or it can be unpriced. Series A: This is the first "growth cycle" a company raises. It will usually have a product in the market that provides value to customers and is on its way to having a reliable and predictable way to invest money in customer acquisition. The company may be about to enter new markets, expand its product offering or target a new customer segment. A Series A cycle is almost always “rated,” giving the company a formal rating. Series B and beyond: During Series B, a company usually gets serious about racing. He has stable customers, income and one or two products. From series B you have series C, D, E, etc. The rounds and the company grow. Final rounds usually prepare a company to go into the black (be profitable), go public via an IPO, or both.For each of the rounds, a company becomes more and more valuable, in part because it gets an increasingly mature product and more revenue as it discovers its growth mechanisms and business model. Along the way, the business also evolves in another way: the risk decreases.

This last element is crucial in how you think about your fundraising journey. Your risk does not decrease as your business increases in value. The company gains in value as it reduces its risks. You can use this to your advantage by designing your fundraisers to explicitly reduce the risk of the "scariest" things about your business.

Let's take a closer look at where risk appears in a startup and what you can do as a founder to eliminate as much risk as possible at every stage of your company's existence.

Where is the risk in your business?Risk comes in many forms. When your business is in the idea stage, you can come together with co-founders who have a great founder-to-market fit. You have identified that there is a problem in the market. Your initial interviews with potential customers all agree that this is a problem worth fixing and that someone is – in theory – willing to pay to have this problem fixed. The first question is: is it even possible to solve this problem?

For a rapid increase in valuation, think, "What is the highest risk right now and how can I remove it?".

Haje Jan Kamps 7 p.m.

You've probably heard of pre-boot, boot, series A, series B, etc. These labels often aren't very useful because they aren't clearly defined - we've seen very small A-series rounds and huge pre-seed rounds. The defining characteristic of each cycle is not so much the amount of money that changes hands as the level of risk in the business.

In the course of your startup, two dynamics are at play at the same time. By understanding them deeply – and the connection between them – you'll be able to make much more sense of your fundraising journey and how to think about each part of your startup journey as you grow. and you develop.

Generally, in broad strokes, funding rounds tend to go like this:

The 4 Fs: Founders, Friends, Family, Fools: This is the first money that comes into the business, usually just enough to start proving some of the core technology or business dynamics. Here the company is trying to build an MVP. In these rounds, you will often find angel investors of varying degrees of sophistication. Pre-seed: Confusingly, this is often the same as the above, except it is done by an institutional investor (i.e. a family office or venture capital firm focusing on early stages of business). It's usually not a "round robin" - the company doesn't have a formal valuation, but the money raised is on a convertible or SAFE note. At this stage, businesses are generally not yet generating revenue. Seed: These are usually institutional investors who invest larger sums of money in a company that has begun to prove some of its momentum. The startup will have some aspect of its operational business and may have test customers, a beta product, an MVP concierge, etc. It won't have a growth engine (in other words, it won't yet have a repeatable way to attract and retain customers). The company works on active product development and pursues product-market fit. Sometimes this round is priced (i.e. investors trade a valuation of the company), or it can be unpriced. Series A: This is the first "growth cycle" a company raises. It will usually have a product in the market that provides value to customers and is on its way to having a reliable and predictable way to invest money in customer acquisition. The company may be about to enter new markets, expand its product offering or target a new customer segment. A Series A cycle is almost always “rated,” giving the company a formal rating. Series B and beyond: During Series B, a company usually gets serious about racing. He has stable customers, income and one or two products. From series B you have series C, D, E, etc. The rounds and the company grow. Final rounds usually prepare a company to go into the black (be profitable), go public via an IPO, or both.For each of the rounds, a company becomes more and more valuable, in part because it gets an increasingly mature product and more revenue as it discovers its growth mechanisms and business model. Along the way, the business also evolves in another way: the risk decreases.

This last element is crucial in how you think about your fundraising journey. Your risk does not decrease as your business increases in value. The company gains in value as it reduces its risks. You can use this to your advantage by designing your fundraisers to explicitly reduce the risk of the "scariest" things about your business.

Let's take a closer look at where risk appears in a startup and what you can do as a founder to eliminate as much risk as possible at every stage of your company's existence.

Where is the risk in your business?Risk comes in many forms. When your business is in the idea stage, you can come together with co-founders who have a great founder-to-market fit. You have identified that there is a problem in the market. Your initial interviews with potential customers all agree that this is a problem worth fixing and that someone is – in theory – willing to pay to have this problem fixed. The first question is: is it even possible to solve this problem?

What's Your Reaction?

![Three of ID's top PR executives quit ad firm Powerhouse [EXCLUSIVE]](https://variety.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/ID-PR-Logo.jpg?#)